- WE SAVE LIVES

- info@wesavelives.org

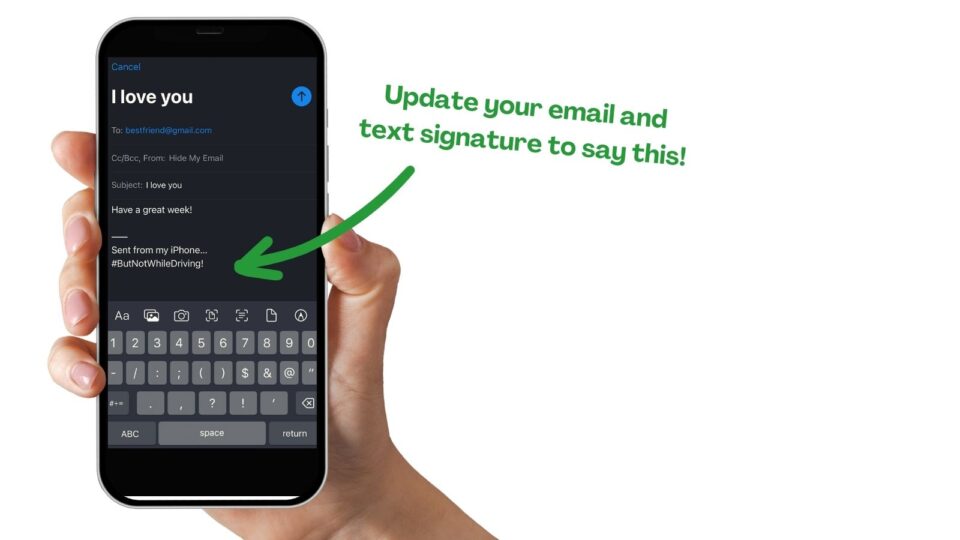

We Save Lives Supports the Textalyzer

October 24, 2017

Drunk Driving Before the Revolution

November 20, 2017Dear Freakonomics Radio Team,

Your May 6th program, The Most Dangerous Machine, relays some seriously irresponsible messages and makes light of a deadly behavior.

As distraction-related fatal crashes in the US rise at an unprecedented rate, host Stephen Dubner and guests lightheartedly assert that “we’ve actually been getting safer,” that “talking on a phone [while driving a car] doesn’t seem to be a very big deal,” that it “does not increase the risk of a crash, and that “it can even be associated with a positive outcome.”

To a backdrop of upbeat music, Dubner leads off the conversation with his friend, University of Chicago’s Steve Levitt, who laughingly admits to being a terrible driver. “I am very distracted as a driver … I talk on the phone and I text … I’m pretty much a walking time bomb when it comes to driving.” Later in the show, Northwestern University economics professor Ian Savage, offers that “cellphones – as disturbing as they would seem to be while you are driving, may also be responsible for saving a lot of lives.” Actually, distracted driving is the primary culprit behind the current unprecedented rise in traffic fatalities in the U.S.

According to Dubner and Savage, though “the raw data might suggest roadway fatalities are rising,” the rate of fatal crashes per mile driven has declined by two-thirds since 1975.

Deaths per 100 miles driven have decreased from 3.45 in 1975 to 1.25 in 2016. However, over the last two years, both number of deaths and fatality rate per 100 million miles driven has increased by 6.8%, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) and the NSC. The millage based death rates helps to control for the increasing number of miles driven in the US from one year to the next.

Dubner and guests assure us that technological and design improvements are winning out, and that distractions are “washed away” by the fact that we are getting better at preventing fatalities. Yet despite technology advances like anti-lock brakes, air bag systems and crumple zones, and despite better engineered roads and more effective emergency services, crashes are becoming more severe – and fatal crashes are rising, according to University of Kansas psychology professor Paul Atchley, who studies driver distraction and the cognitive effects of in-vehicle technology.

Hundreds of driver distraction studies over five decades point to phone use behind the wheel as a behavior that impairs cognitive function, significantly undermines driving performance and raises crash risk. Talking on a phone, hand-held or hands-free, quadruples the risk of a crash to a level at least equal to that of driving drunk, according to naturalistic driving studies conducted by University of Utah cognitive scientist David Strayer.

Dubner must be familiar with these statistics, as well as with research from Strayer and the AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety demonstrating that the brain remains distracted for up to 27 seconds following a call or text (including hands-free, voice-activated systems).

Yet Dubner doesn’t challenge Fitch when he asserts that “whether a driver is holding the phone or not, talking on the phone – while not recommended – does not increase the risk of a crash.” Nor does he flinch at the professor’s suggestion that phone use may even be associated with a positive outcome: “It’s been proposed that talking on the phone actually reduces boredom. There’s been research that shows that people are more awake, more alert up to 20 minutes after having a cell phone conversation. Kind of like, you know, drinking a cup of coffee or taking a caffeine pill.”

Dubner pauses only briefly before rolling into the next segment of the piece: “It’s nice to know that driving has gotten relatively safer – but remember, there are still 1.2 million traffic deaths a year worldwide!” His careless tone disregards an issue that has been clearly identified as a worsening public health epidemic. How does this kind of programming serve your mission of creating a more informed public?

Alyson Geller

We Save Lives Advocate