- WE SAVE LIVES

- info@wesavelives.org

Guest Blog: Distracted Driving & Technology: It’s Not What You Think It Is—It’s Much Worse

Hailey Brooks

June 22, 2024

We Need To Save More Young Lives Driving on Our Roads

July 17, 2024 Guest Blog Post by Mi Ae Lipe

Guest Blog Post by Mi Ae Lipe

Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve heard that distracted driving is dangerous. Perhaps you’ve seen electronic signboard messages warning against it on our highways or heard it covered in the media.

Perhaps you even do it yourself behind the wheel—talk on the phone, text, play Pokémon Go, use Snapchat, check Facebook or email on your smartwatch, or fiddle with the GPS and infotainment systems in your car.

You might think nothing of it: I’m a good driver. I’ve done it many times and nothing bad has ever happened. I only do it when I’m at a stoplight, anyway. It’s the other idiot whom I have to watch out for.

Well, it’s time to stop, because the problem is far more serious than you think. And you’re already paying for the actions of distraction drivers in ways you never imagined.

Why Is Technology So Unsafe?

Often-cited driver distractions include eating, grooming, wrangling children, talking to passengers, fussing with pets, and falling asleep. But the biggest elephant sitting in the driver’s seat is electronic technology—specifically smartphones, wearable devices, and in-car systems that allow us to access email, apps, games, social media, texting, cameras, and the Internet.

You might be asking: What’s the big deal? Why not also ban reaching for a water bottle or fiddling with a radio? Or listening to music?

The key difference with electronic technology lies in the cognitive load. We think we can multitask but we can’t—our brains simply switch back and forth very quickly. Ever notice how people walking while talking on cell phones suddenly stop moving when they’re in deep conversation? Their vision literally deadens in a phenomenon called inattention blindness, because their brains can’t handle the two tasks at once. The same thing holds true behind the wheel: Our minds cannot be fully focused on the task of driving a two-ton vehicle while we’re doing something else.

Besides the cognitive load, electronic tech demands our visual attention (our eyes are on the screen and not on the road) as well as manual attention (at least one of our hands is not on the steering wheel).

What makes tech especially dangerous is our desire to engage with it so compulsively. Biologically, we’re wired to crave social connection and information. An incoming call or message is the proverbial tap on our shoulder, as Matt Richtel writes of the neurocognitive science in his 2014 book A Deadly Wandering. Ours is a perpetual reward system—answer that siren call, and our brains release dopamine, a neurotransmitter that activates our pleasure centers. Respond again, and we get another little dopamine squirt. Once habituated, our brains crave more, getting restless when deprived of stimulation for too long before its next fix.

Based on this neuroscience, this is why so many entreaties to not use our cell phones when driving simply don’t work. It’s not simply behavioral—it’s about overcoming a chemical addiction of sorts (or at least a very strong biological compulsion).

Consider these facts:

- On average, texting drivers take their eyes off the road for up to 5 seconds at a time. At 55 mph, that’s traveling the length of a football field completely blind.

- Drivers talking on the phone can miss up to 50 percent of what’s in their driving environments.

- It’s not safe to use a device even when stopped at a traffic light; University of Utah researchers have found that drivers can take up to 27 seconds to regain full attention after sending a text.

- Despite popular belief, hands-free and Bluetooth operation aren’t safer—that cognitive load is still present.

The True Cost of Distracted Driving

In just the past two years, the number of people seriously injured or killed distracted by technology has skyrocketed. According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), fatal crashes suddenly jumped nationwide by 7.2 percent in 2015, and 2016 preliminary statistics are not looking much better. The National Safety Council estimates that cell phone use is a factor in 1 out of every 4 collisions in the United States.

Every day in the United States, at least 8 people die in crashes involving a distracted driver, according to the Centers for Disease Control. That’s 2,920 people or 7 jumbo jetloads of dead passengers every year—and that’s not including nearly 424,000 more injured.

And the carnage is not just confined to drivers and passengers—it’s also pedestrians, cyclists, and other road users. In 2015 alone, pedestrian fatalities jumped nearly 10 percent to 5,376, and injuries increased nearly 8 percent to 70,000, according to NHTSA. That amounts to a person dying nearly every 2 hours. For our roads to be safe, all its users need to be distraction-free.

Children and adolescents are particularly vulnerable because they often think it’s okay to wear headphones and use electronic devices when crossing the street, and drivers think it’s fine to use their smartphones in school zones and other places. In a 2014 study, nearly 40 percent of the 1,040 American teens participating reported having been hit or nearly hit by a passing car, motorcycle, or bike.

Aside from the obvious tragedy, the financial impact on the American economy is profound. In a 2015 report, NHTSA calculated the average lifetime economic cost for each fatality as $1.4 million, with over 90 percent attributable to lost workplace and household productivity and legal costs. Crashes in which at least one driver was identified as being distracted cost a staggering $40 billion in 2010—all of it preventable.

Not surprisingly, insurance companies are also feeling the effects of distracted driving and passing it along to all their customers. Their loss costs—payments to treat injuries, repair damaged vehicles and property, and defend insured drivers in legal actions—have soared since 2011, resulting in the average annual auto premium jumping 16 percent to $926. Much of that increase is directly related to texting and driving. Distracted drivers often don’t admit to using their tech; thus, no fault can be attributed in many collisions.

So you and I end up paying these costs, even if we’re responsible drivers ourselves. How fair is that?

But What If? And What About My Rights?

You might be thinking: But what if I have an emergency and need to call or message back while driving? The neurocognitive research shows that our biology has superbly trained us to be slaves to our technology by creating a false sense of urgency, desire, and reward.

It’s time to think of electronic distraction as the new drunk driving because our smartphones are the ultimate open container.

As a species, we’re really good at being overconfident and incredibly poor at gauging risk. Danger is abstract because most days nothing happens. We’re not good at grasping consequence until we’re staring at its aftermath. And that aftermath can be incomprehensible. Deaths and injuries from distracted driving are alwayspreventable. No call or text or game or selfie is ever worth the untold anguish. Period.

As a society, we’re often very resistant to legislation and enforcement efforts against smartphone and electronic tech use behind the wheel. But at stake are lives, well-being, property, and the economy. Personally, I’d love the right to drive without fear of someone on their phone crashing into me, or my children to walk across the street without the threat of being killed or injured by an oblivious red light runner, or not have to literally pay for the follies of others. Who knows, you just might too.

What You Can Do

Contact your legislators. Advocate for consistent laws, education, enforcement, cultural stigma, and swift, heavy penalties. Pledge to make cell phone use while driving as socially inacceptable as drunk driving. Make it a priority that you won’t enable yourself or others to perpetuate this dangerous activity. Don’t talk to someone on the phone if you know they’re driving.

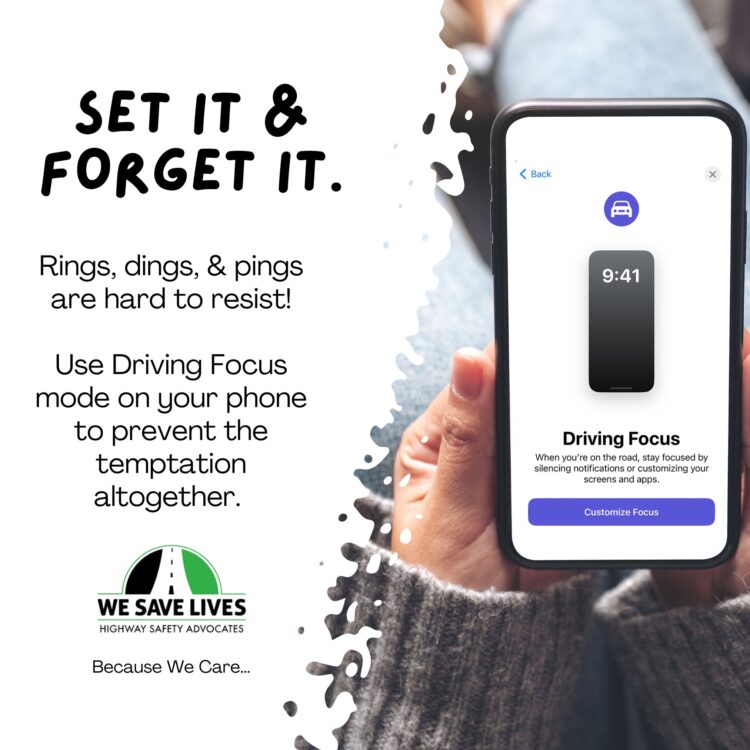

The single best way to overcome temptation? Shut off your phone completely and put it where you can’t reach or hear it, like in the trunk. If you must use GPS, input addresses before you start moving. If you need to adjust it, wait until you’re safely stopped.

And remember, you’re always modeling behavior for your children as well. By the time they’re driving age, they’ve had at least 15 years of seeing what you do behind the wheel—a little late to tell them “do as I say, not as I do.”

Mi Ae Lipe is a citizen advocate and We Save Lives Partner. She blogs on Driving in the Real World, Tweets daily driving news and tips at @DrivingReal, and writes a regular column on street driving for BMW CCA’s Roundel magazine. Visit her website to download her free eBook “The Sound of No Car Crashing: A Guide to Protective Driving”.